I'm just getting over being sick. Which has been an ordeal—for everyone around me.

I’m a difficult patient.

I’m impossible to please (“soup shouldn’t be this hot!”), irritable (“juice shouldn’t be this cold!”), and even when my wife was rubbing my back, I complained (loudly, bitterly) that she has all the gentleness of a longshoreman. So rude!

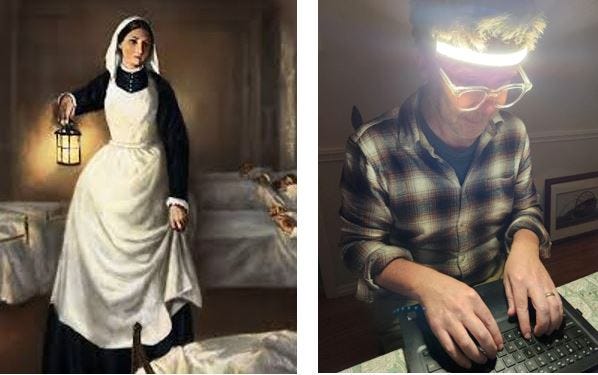

I’m the kind of patient Florence Nightingale would take one look at and write “LFFTD” (actual medical shorthand for: “Looked Fine From The Door”) in my chart before walking away and going on break.

But in my feverish hallucinations this past week, I spoke to Florence Nightingale about how she raised money and got an entire country to start paying attention to social problems with their heads, not just their hearts. Which is what good fundraisers do, too.

Welcome to this week’s fever dream, you guys.

Here’s your crash course on Florence Nightingale, Substack:

Smack dab in the middle of the nineteenth century, Florence Nightingale served as an Army nurse treating the British sick and wounded during the Crimean war (1854-1856). She fought to improve sanitary conditions at military bases and hospitals—which put her at loggerheads with the War Department brass, but also turned her into a national hero. (Note: quotes for this post are from Mark Bostridge’s Florence Nightingale: The Making of an Icon.)

Letters home from wounded soldiers coupled with testimonials about Nightingale’s compassionate nursing became mainstays of press coverage of the Crimean War, transforming her into a national celebrity when she returned home in 1856.

The image of Nightingale attending to patients by the light of a single lamp led to the “The Lady with the Lamp” reputation you’ve heard about but never knew where it came from.

SIDEBAR: “Florence Nightingale Syndrome” & Athena the Owl

“Florence Nightingale Syndrome” occurs when a caregiver falls in love with his/her patient. It never actually happened to Nightingale. I, however, suffered from the first known case of “Reverse Florence Nightingale Syndrome:” everyone in my house hates me when I’m sick.

Fun fact: Nightingale kept an ill-tempered pet owl named Athena. I have a bad-mannered dog named Jasper who eats hamburgers off my plate without asking. So, you know. Same-Same.

When Nightingale returned to England, the country raised upwards of £45,000 (roughly $6.5 million today) for something called “The Nightingale Fund.” Nightingale didn’t ask for the money or know what to do with it. By 1860, she used much of it in founding the Nightingale Training School for Nurses at St. Thomas’ Hospital in London, providing young women with training and new career opportunities.

It’s a fascinating moment in fundraising history that doesn’t happen very often: people give you money simply because they believe you’ll do the right thing with it. Bostridge calls it “Nightingale Power” (316) but also an example of people giving to people, like we’ve talked about here and here.

I’m giving you all this background because I’m about to bring this heat:

Nightingale was an amateur statistician of some repute and apparently was among the first people in the nineteenth century to use data and statistics as part of public fundraising and reform appeals.

Don’t believe me? Check out the Statistics textbook below (hat tip to Debbie T. for calling my attention to this):

Nightingale wanted people to feel differently about something—say, Army health reform—but she also wanted them to think differently about it, too. Bostridge sums up her approach as “the careful marshalling of the most accurate raw data and, if this was unavailable or inadequate, the dispatch of questionnaires to obtain it, together with the enlistment of the finest expertise to help understand and formulate solutions” (315). In other words: Go out, collect the data, analyse the information, and use it to solve problems. Both with your head and your heart.

Nightingale spent her post-Crimea life working to collect and present the data that would convince government officials, Army generals, philanthropists, and the larger medical community of the need for trained military nurses, larger spaces in hospital wards, and for the connection between better sanitary conditions and health care. And she did it by appealing to both the head and to the heart.

We have in Nightingale a forgotten model for our own behavior as fundraisers. Somebody capable of combining the head and the heart in the appeals she makes.

A nineteenth century model for twenty-first century fundraisers.

In closing, I’m a terrible patient. I know this about myself.

But I’ve learned that Florence Nightingale was a bad patient, too.

Near the end of her life, her family hired a nurse to attend to her: “When the nurse had tucked her up for the night, she would often reverse the parts, get out of bed and go into the adjoining room to tuck up the nurse” (518).

Same-Same.

So, I guess what I’m trying to say is, I think I’m the second coming of Florence Nightingale, you guys. No, seriously.

It’s either that or I still have a raging fever and am hallucinating that I am, in fact, the reincarnated embodiment of a Victorian woman who championed statistical data into fundraising and public health appeals.

Either way, I’m heading back to bed where nobody in this house will do anything to make me feel any better so I might as well just die.

See you next week.

OMG you are SUCH a drama queen!

One of the first chapter book biographies I read was on FN. Thoroughly enjoyed this piece Dan. Thank you!