A recurring feature of this Substack has been posts exploring famous people across history who raised money without always knowing what they were doing:

A few of these posts are excerpted from a book I’m writing, titled The Elegant Fundraiser’s Guide to Train Robbery. It’s about famous, well-meaning people who fundraised by the seat of their pants, did a lot of stuff wrong, yet still managed to raise the money that changed the world.

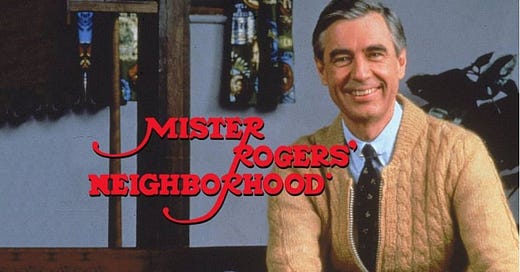

This week’s post is from my chapter on Fred Rogers (of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood fame).

He could step into the role of fundraiser as casually as breezing through a doorway, donning a colorful sweater, and slipping into an old pair of sneakers.

Readers of a certain generation need no introduction to Mister Rogers. For anyone who doesn’t know, when it first premiered in February 1968 on WQED in Pittsburgh, Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood was unlike anything else on children’s television. With puppets and songs set against the backdrop of the Land of Make-Believe, Rogers validated what children feel and experience in an unpredictable world.

Less than a year into his program, Rogers was unwittingly thrust forward to raise money for Public Television after the Nixon administration wanted to reallocate its funding to the conflict in Vietnam. At the time, Public Television’s $20 million appropriation was controlled by the chair of the Senate Subcommittee on Communication, the pugnacious John O. Pastore (D-Rhode Island).

Pastore took a dim view of television. The New York Times reported in November 1969 that Pastore’s “bite has made broadcasters noticeably jumpy in recent months” and his palpable irritation during the first day of testimony didn’t bode well for Public Television’s appropriation.

Those responsible for Pastore’s bad mood were Public Television’s executives and, by extension, its principal fundraisers. Throughout the hearings, Pastore repeatedly implored witnesses to “just give us the salient points.” Ignoring their assignment, these fundraisers rattled off statistics from prepared scripts, thundered away at the importance of public television, and gave dry explanations for how children process what they see on the screen.

Pastore finally cried mercy.

Nobody, he growled, was to read anything at him anymore.

Of course, Pastore announced this just before Rogers was set to read his prepared remarks.

Tabling his script and instead speaking extemporaneously with that slow western-Pennsylvanian lilt, Rogers explained what each episode of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood accomplishes:

I feel that if we in public television can only make it clear that feelings are mentionable and manageable, we will have done a great service for mental health. I think it is much more dramatic that two men could be working out their feelings of anger, much more dramatic, than showing something of gunfire

There was no longer any gunfire coming from Pastore and his voice lost its sharp edge when admitting “this is the first time I have had goose bumps for the last two days.” Pastore’s feelings had, suddenly, become “mentionable and manageable” because of the candid expression of care that Rogers’ show—and by extension, Public Television—provides viewers.

To conclude his testimony (which clocked in at a mercifully brisk seven minutes), Rogers spoke song lyrics that inspire children to better control their own feelings:

‘What do you do with the mad that you feel? […] When the whole wide world seems so wrong and nothing you do seems very right? […] Do you punch a bag? […] Do you round up friends for a game of tag or see how fast you go? It’s great to be able to stop when you have planned a thing that’s wrong, and [be] able to do something else instead and think of this song…’

Rogers’ earlier point about “two men […] working out their feelings of anger” coupled with these lyrics about anger management gesture to his larger point about the social-emotional training young viewers need to become healthy citizens. Was Pastore willing to take a leap of faith with this soft-spoken broadcaster who believed public television could educate a weary nation about its own feelings?

When Rogers finished, Pastore—his voice soft and dreamy—concluded: “I think it is wonderful. It looks like you just earned the 20 million.”

Without exactly knowing what he was doing, Fred Rogers was the right person to do the asking. In the chapter-version of this post, I break down what lessons we can glean from Rogers’ experience, including: why it’s important to avoid this speed-dating approach to fundraising, how Rogers’ improvisation is harder to pull off than it looks, and the importance of building relationships after a gift is made.

Learning how Fred Rogers, Mark Twain, Helen Keller, and Florence Nightingale raised money reinforces a stunningly simple point about fundraising: that you don’t always need to do everything by the book to make your fundraising a success.

Mister Rogers liked you just the way you are. And he’d probably tell you to go out and raise money for things just the way you are, too.

A simple lesson from the past that bears repeating in the present.

Mister Rogers certainly had a way with children and people; genuine, kind and accepting. If we could all be that way.

Great article!

When you come for a visit, we can take a trip to Mr. Rogers' neighborhood. It is about 50 minutes away. As i recall your wife watched often. Good post.